Ad Blocker Detected

Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors. Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

From Kon Tum city, we had to continue more than 100 kilometers to reach the town center of Dak Glei district. The car was hot because of the steep sections around the Ngoc Linh mountain range. This mountain is more than 2,600 meters high, symbolizing the majesty of the Central Highlands and the resilient will of the Xe Dang, Gie Trieng, and Hre people. Vast green forests and the fragrant scent of coffee flowers on the fields from afar…

The winding pass of Mang Khen and the prison are associated with poet To Huu

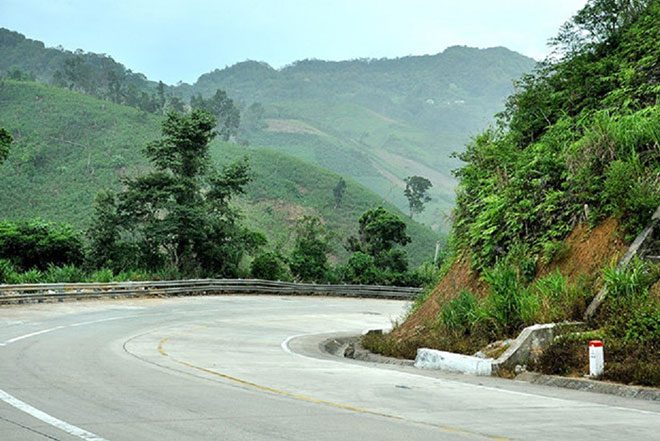

Before reaching Dak Glei, the convoy had to pass a pass close to Mang Khen village (Dak Choong commune). People named it Lo Xo Pass because every few minutes there is a curve going up. The pass is up to 20 kilometers long and at an altitude of thousands of meters. Many large trucks have caught fire when going down a mountain pass because they continuously used the brake pedal every time they turned a corner.

The overheating caused the motor to explode and the fuel tank to catch fire. This pass is called “t t t t t” because of that. Yet during the war against America, this pass was the lifeline on the Ho Chi Minh Trail for our army to transport food supplies, weapons and ammunition to the southern front. Previously during the French colonial period, Lo Xo Pass was also an ambush site in the mountains to attack the enemy of the Central Highlands people. This pass is the grave of French colonialists during the years of resistance since the early 40s.

To build Road 14 extending from Kon Tum city to Dak Glei, the French colonialists forced ethnic people to carry stones to build the road (from 1927 to 1930). From high posts on Dak Glei, they can block the roads from Quang Nam and the national highway from Laos.

Spring Pass has a bend in the sleeve.

The mountains here are dangerous with wild animals lurking, but they also contain hidden dangers when guerrillas attack very suddenly. So by all means they have to build roads to take artillery vehicles up high mountains. Thousands of laborers have to work day and night. Anyone who refuses to go to work will be arrested and imprisoned at the top of Lo Xo Pass. At first it was just a small prison shack. After the number of prisoners increased, the French invaders built large houses. Dak Glei Prison was formed from there (1932).

But the French enemy did not expect that, the resistance movement became increasingly stronger from 1936 to 1940. More and more guerrilla armies appeared. Revolutionary forces mature everywhere. The French invaders tried their best to suppress and arrest revolutionary soldiers. They had to build a sturdy house made of stone to detain people with life sentences. Those can be considered the first political prisoners in Dak Glei.

Among them were movement leaders such as Nguyen Duy Trinh, Huynh Ngoc Hue, Chu Huy Man, Le Van Hien, Tran Van Tra and especially poet To Huu. But in preparation for the Viet Minh General Uprising, poet To Huu and comrade Huynh Ngoc Hue were secretly organized to escape from prison (February 1942).

After 20 days and nights, the poet was protected and raised by the ethnic people, leading the way to escape from the vast wilderness. In 1973, poet To Huu had the opportunity to go on a business trip, return to Kon Tum and visit the old battlefield. He wrote the poem “Thousand miles of mountain water”, which contains verses recalling the Xe Dang and Gie Trieng ethnic people who helped him.

He wrote: “Oh my little Ro village/ High mountain, eagle’s cradle/ For a hundred years I have been grateful to the village/ The arm protecting my dangerous journey/ I love you My River girl/ Holding sticky rice to send me off through the forest…”. Later, Dak Glei prison was also given the name “To Huu Prison” by the Central Highlands ethnic people.

Hero Dak Glei

It was the vast forest that poet To Huu was protected by his relatives that served as the background for Nguyen Trung Thanh (writer Nguyen Ngoc) to later write the short story “Xa Nu Forest” (1965). The character Old Met is a symbol of a real-life hero (Mr. A Met) in the resistance village of Xop Dui (Dak Glei).

The story is fictional and changes the name of the village and related things because at that time the village was still under the control of the American invaders. Even the tree’s name like Xa Nu was replaced with three-leaf pine at the resistance base. If we stand above Dak Glei prison and look down, we can see vast green pine forests before our eyes.

The stories of the hero A Met seem so legendary. Because his way of fighting the French was very strange and daring. A Met (Xe Dang person) real name is Dinh Mon (1913-2000), who mobilized the villagers of Xop Dui to rise up to fight against the French invaders very early.

The A Met army’s battle uniforms were filled with spears, bows and crossbows. Yet, from hiding places on top of slopes or setting traps in the valley, the martyrs destroyed many enemy groups that entered the village. The soldiers’ very accurate archery and crossbow skills defeated dozens of them without much effort. As for the bowman A Met, he missed every shot. Every shot hit the enemy’s eye.

The poison quickly seeped into their bodies, and the enemy fell to the ground dead. From then on, the brave soldiers captured weapons and ammunition from the French enemy and collected them for use. A Met’s demonic possession made the enemy crazy. They didn’t know A Met’s face, so they offered a big reward to anyone who captured him, or even surrendered A Met’s head.

One day, a man wearing a camouflage officer’s uniform entered the French station and told him to capture A Met to receive a reward. This person boasted about where A Met was hiding. The French enemy army trembled and pulled away. The zigzag road led near the mountain cave when the other officer turned around and shouted: I am A Met! Then disappeared behind a large rock. Unexpectedly, that was an order.

Arrows and bullets shot out. The French enemy could no longer turn back because they fell into A Met’s trap. More than a dozen blunt-nosed arrows died instantly. There was a time when A Met himself had malaria and lay down on the street in a neighboring village. The French enemy on patrol saw this and thought it was a dead Xe Dang man, but maybe it was the A Met they were looking for.

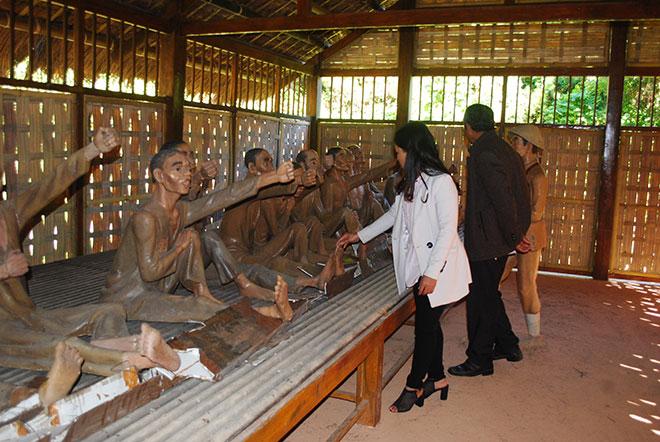

The display depicts the imprisonment of revolutionary soldiers in Dak Glei prison.

The villagers were forced by the enemy to carry this body and throw it into a mountain cave for the tigers to eat. The next day, people passed by and looked up at the cave to see A Met sitting rolling cigarettes and smoking. They panicked, thinking it was a ghost seeking revenge, so they ran away. He shouted loudly: I am A Met, not a ghost. He patted his chest and laughed loudly, echoing throughout the mountains and forests.

In 1949, comrade Tran Kien at that time went to Xop Dui to admit A Met into the Party and then established an armed guerrilla team. A Met was also assigned to be the District Captain of Dak Glei. With his exceptional command talent, A Met organized the army to arrange many battles against garrisons to confuse and fear the enemy.

In 1954, A Met was sent to the North to study and improve his combat command level. Returning, he became Secretary of the Xop Dui commune cell. Even the American enemy later could not capture him. Every time A Met goes into battle, it brings unexpected victories. Many areas of Xe Dang and Hre people are free. The enemy did not dare to approach.

In 1972, A Met was also elected Secretary of the H30 District Party Committee (Dak Glei). He continued to contribute to commanding troops to fight the American enemy until the day the entire Dak Glei district was liberated (May 16, 1974). Later, A Met was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the People’s Armed Forces. This is a worthy honor of the Party and State for the hero of the Kon Tum mountains and forests

Xe Dang lullaby

Ngoc Linh primeval forest always resonates with the sounds of birds chirping and gibbons singing. A jubilant nature song at dawn. The clouds gradually dissipated, revealing the green canopy of trees. The waterfall on Lo Xo Pass flowing from above becomes clearer and the white water spray covers the entire area. The quiet moments of the wind began with the lullaby of young mother Xe Dang in the hammock.

Perhaps they will forget the hustle and bustle of footsteps leading the way for vehicles traveling at night. They can forget the days of carrying bullets to the front and the nights of raiding enemy posts on top of the pass… Mothers return to their lullabies for their children.

The village is sweet in its lyrics: “Sleep well, my dear.” Far away in the forest, my father is picking young bamboo shoots. Sleep well, my dear. Somewhere far away, my mother found young vegetable shoots. Don’t cry anymore, my dear” (Xe Dang folk song). That’s right! Dak Glei is just that. Peace and happiness.